Understanding the mechanics of global supply chains

NSF-supported researchers study how to fix – and break – global networks

The global supply chain is key to keeping society humming, making sure that manufacturers have what they need to get products like medicines, computer chips or Christmas toys to market. With the COVID-19 pandemic now affecting supply chains across the world, the research that helps us understand how these networks function is even more critical.

Governments are always looking for ways to bolster legal supply networks – and disrupt illicit ones. The U.S. National Science Foundation is a leader in both efforts, supporting proactive and award-winning research that's saving lives and livelihoods, protecting people and wildlife, and identifying network resiliencies and weaknesses.

"I think this pandemic has really laid some things bare," said Georgia-Ann Klutke, a program director in NSF's Engineering Directorate. "By dislocating supply and demand, it pointed out how vulnerable we are and how dependent we are on global supply chains. That's where NSF can start to look at what's going on and how we can do better."

Shock and resilience

Earlier this year, President Joe Biden signed an executive order requiring federal agencies to find ways to strengthen and secure America's complex and often opaque supply chains. The order called for reviews of critical networks in areas of defense, energy, transportation, public health and biological preparedness, information and communication, and the U.S. food system.

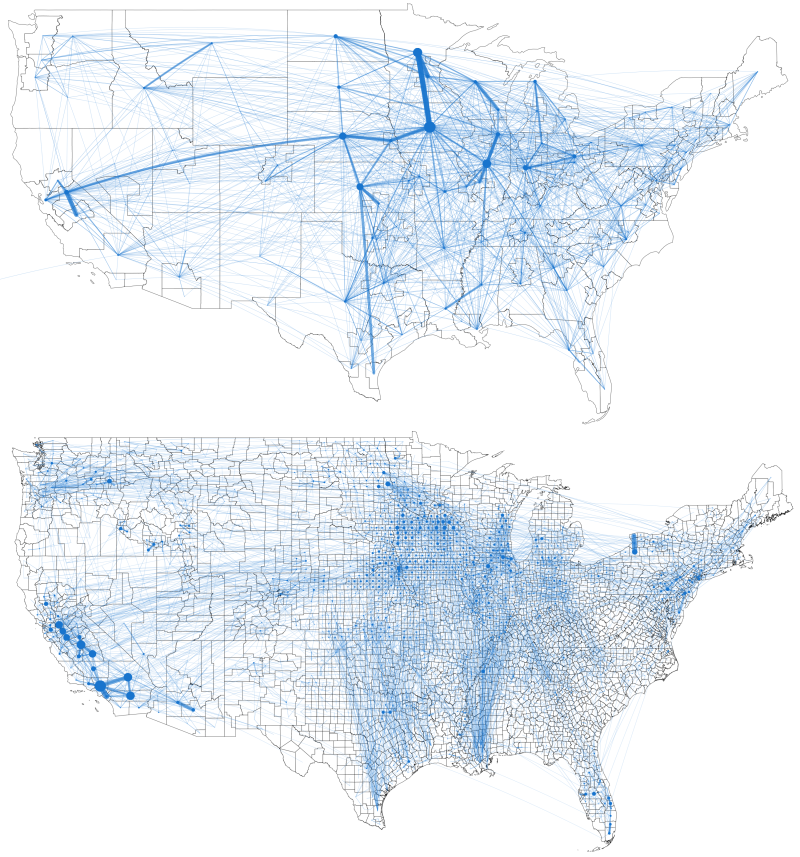

With NSF's support, Megan Konar, a civil and environmental engineer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, is working to help secure the U.S. food production and supply chain. For several years, Konar and her team have been building on a rich body of research to understand where and how food is moving throughout the country and the network's resilience to water use issues, climate hazards, cyberattacks and degraded infrastructure. Her research has now expanded to include the impacts of a pandemic on the system.

"The pandemic was a pretty significant shock to our food supply chains," Konar said. "All of the 'eat-away-from-home' supply chains were impacted. But even with such a large shock, I was pretty heartened and impressed with how adaptable the food supply chain was."

Konar is identifying "hot spots," or chokepoints, in supply networks and expects to respond to Biden's executive order by year's end.

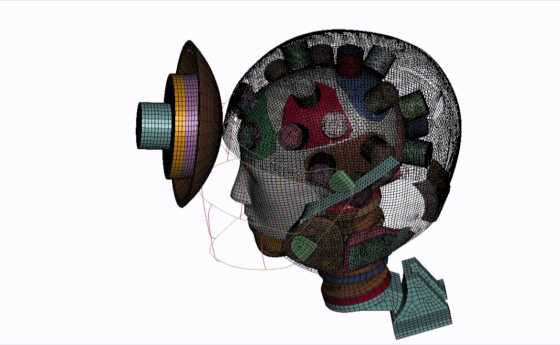

Meanwhile, Kira Barton, a mechanical engineer at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, just launched new research into an "intelligent agent" approach to make global supply chains more resourceful and efficient.

The idea is to use virtual agents in a computer model to represent components throughout a supply chain, from raw material suppliers to end users, to communicate and negotiate with each other, improve operations, manage risk and lower costs. Barton plans to validate this approach through a real-world case study in automotive manufacturing.

The disruptors

The dark side of supply chains includes the trafficking of counterfeit goods, drugs, wildlife and humans. NSF collaborates with the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security as well as academic researchers to devise ways to identify and dismantle such illicit networks.

Louise Shelley is a sociologist at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and founding director of the school's Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center. Earlier this year, Shelley and her team – together with Damon McCoy, a computer scientist at New York University – began collaborating with the 3M Company to identify and break up international networks that were importing bogus personal protective equipment into the United States.

Within months of receiving NSF grants last October, the team's data analysis enabled law enforcement to seize more than 52 million fake N95 masks and more than 2 million counterfeit respirators bound for medical facilities in a state decimated by COVID-19. Their work has contributed to the seizure of 55 million counterfeit masks worldwide.

The team's work has led to the removal of tens of thousands of web pages and social media posts supporting the illegal trade. A key component of illegal trafficking, Shelley said, is the number of legitimate businesses – like tech companies – that, wittingly or not, facilitate it.

That successful partnership recently led World Trademark Review magazine to grant 3M its 2021 North America Team of the Year Award.

Shelley also works to disrupt other illicit trade, including trafficking of humans and of fentanyl and other narcotics. She is applying lessons learned from the tenacity and innovation of traffickers in getting goods shipped and delivered to strengthen legal supply chains.

Dismantling human trafficking networks is a focus for Thomas Sharkey, an industrial engineer at Clemson University. Sharkey is helping to lead a team of academic and law enforcement experts as well as an advisory group that includes human trafficking survivors. Together, they're working on ways to counter other illicit behavior related to human trafficking, such as forcing victims to sell drugs or recruiting more victims to replace those that are rescued.

"We're starting to scratch the surface to try and take a holistic view of intervention, including addressing the basic social welfare needs of potential victims," Sharkey said. "To understand how all these potential interventions work together or should work together and collaborate – and focus on making it better for the victims."

Combatting wildlife trafficking

For conservation social scientist Meredith Gore at the University of Maryland, victims of illegal global trade are animals like pangolins, turtles, snakes, songbirds, sea cucumbers, elephants and rhinos, some harvested and trafficked to the brink of extinction to fuel an annual global criminal economy of about $23 billion.

Gore has projects on five continents – places such as Madagascar, Mexico, Vietnam and Ethiopia. But wildlife trafficking isn't confined to foreign lands. The U.S. is a destination, transit point and source of trafficked flora and fauna.

"Every single state in the U.S. has wildlife that's being taken," Gore said. "It undermines the rule of law. It reduces our tax revenue. And then who are these people? The high-level criminals are often associated with organized crime."

But some are businessmen who traffic on the side. Reptile wholesaler and convicted wildlife smuggler Michael Van Nostrand, for instance, nicknamed “The Lizard King” in a 2008 bestseller, was just charged with conspiring to smuggle illegally harvested wild Florida turtles to Asia, where they're used for meat, medicine and as pets. If convicted on these new federal charges, Van Nostrand faces up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

With NSF support, Gore is combining computer science, operations engineering and conservation social science to better understand and predict such illegal networks, and how, when and where to intervene and disrupt. She calls such an interdisciplinary approach "conservation criminology," and believes prevention, more than response, is key.

"Crime response is great," Gore explained. "If my cell phone or car is stolen, I have insurance. But when we're talking about natural resources, once a tree is cut, it's cut. Once a rhino is shot, it's shot.”

For Klutke, the key to understanding any supply chain is transparency – but that's also in short supply. And that's where adopting new approaches and more research can help.

"We can do a lot more analyzing what the digital footprint of material flows look like and then using that to try to understand what the connections are," she said. "Because it's a big network, and we don't see the entire thing. Getting greater visibility is something researchers can really make some progress in."