Shrimps go big – and go Hollywood

DiCaprio and Kutcher invest in NSF-funded startup turning shrimp shells into biodegradable packing foam

Packing foam is forever – it can't be recycled, and its petroleum-based plastic components can persist in the environment for centuries. With packaging waste making up about one-third of total U.S. waste every year, it's a major challenge.

Engineer and entrepreneur John Felts has an intriguing solution: shrimp shells.

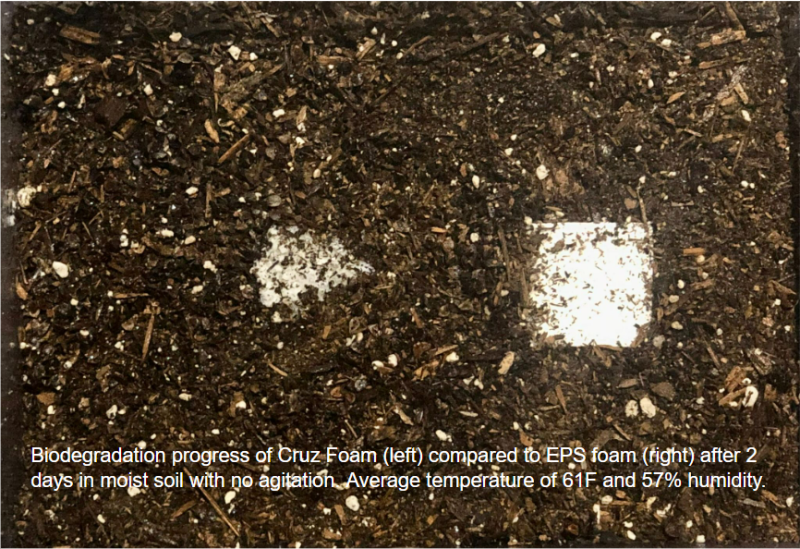

Felts and his partners devised a way to harness the chitin from shrimp shells discarded by the seafood industry and convert it to a foam material that's as lightweight, tough and moldable as the familiar, petroleum-based version, commonly known as Styrofoam. The difference? The shell-based material quickly and harmlessly biodegrades after use – even in your own yard.

The U.S. National Science Foundation enabled the team to refine its technology, bring their idea into the world and kick-start the Santa Cruz, California-based startup, Cruz Foam. This great idea recently attracted two investors famous in environmental activism and film: Leonardo DiCaprio and Ashton Kutcher.

Said DiCaprio in a statement, "The mission to eliminate single-use plastics in the ongoing battle for a cleaner and more sustainable environment makes me excited to join as an investor and advisor."

Said Kutcher, "We see huge potential in the adoption of Cruz Foam's consumer packaging as the industry moves away from petroleum-based products and towards new biomaterial technologies."

For Felts, "having their validation is really just a cherry on top to show that this is happening."

Small shrimp, big impact

Chitin, pronounced KITE-in, is an abundant natural polymer found in the shells of crustaceans, insects and the cell walls of fungi. Felts said he opted to source from shrimp shells because they have the highest percentage of chitin per mass, and thousands of tons literally go to waste every year from seafood operations.

Chitin can be used to produce a number of biomaterials to replace single-use plastics, but Cruz Foam will begin with a bio-alternative to expanded polystyrene packing material, or EPS.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 14.5 million tons of plastic containers and packaging, which includes EPS, were generated in 2018. The same year, less than 14% of plastic waste was recycled, less than 17% burned for energy, and nearly 70% ended up in landfills.

Felts was introduced to chitin while a graduate student in engineering at the University of Washington. His advisor in the materials department, Marco Rolandi, was exploring a possible medical use. That idea was eventually dropped, but Felts and Rolandi, both avid surfers, had a "lightbulb moment" about using chitin to manufacture surfboards, which are almost all made of high-performance plastic foam that too often ends up as ocean trash.

"The idea of being ocean-lovers but riding around on trash felt really strange," Felts said. "And why is nobody looking at bioplastics in a structured foam application?"

They knew a chitin-based surfboard wasn't a scalable business model, but packing foam was – and it could have a big environmental impact. They relocated to Santa Cruz in 2016 and in 2018 secured an NSF Innovation Corps grant for $50,000 that enabled them to understand the commercial potential of their work. I-Corps fuels entrepreneurship by helping scientists and engineers explore how to take their research or promising idea to the marketplace.

The following year, a $225,000 SBIR grant from NSF helped them develop their first prototype, hire staff and, most importantly, raise outside investment capital. SBIR, known as America's Seed Fund, supports the most promising early-stage research and development proposals. In March, both SBIR and I-Corps were folded into NSF's newest directorate: Technology, Innovation and Partnerships, or TIP. In 2021, Felts and his team secured a SBIR Phase II grant for more than $1 million. That support helped them expand into a 5,000-square-foot pilot production facility to fully develop a technology suite that they can take to commercial partners like the Whirlpool Corporation.

Their business model isn't to produce the product, but to show commercial partners how to retrofit or repurpose their existing plastic manufacturing to biomaterials.

But will the packing, to be blunt, stink?

“Absolutely no smell whatsoever. At all,” said Felts. “Another question we might get is, ‘Does it cause shellfish allergies?’ And the answer is also, ‘No.’”

He explained that shrimp shells are made of minerals, proteins and chitin, and it’s the proteins that cause allergies, not the chitin. They only use the chitin – no proteins – to make the foam.

Felts said Whirlpool may be using Cruz Foam packing material as early as next year, while other potential commercial partners are in the pipeline in the construction, automotive, beverage and electronics industries.

The company also secured funding from investment vehicles like Sustainable Ocean Alliance, At One Ventures, Regeneration.VC, the Sony Innovation Fund and SOUNDWaves, which back promising environmental startups. Kutcher is investing in Cruz Foam as a co-founder of SOUNDWaves; DiCaprio is investing directly. Felts recently held in-person meetings with each.

"It's really cool when you see these guys that are almost larger than life being really engaged and really excited and really seeing the precipice of change in front of us when you look at climate change," Felts said. "It's definitely a defining moment for the company."

"We love to see that other investors and other partners will jump in because then we can move on and fund the next great company, and they can move on to the next stage of their journey,” said NSF Program Director Ben Schrag.

More green packaging

NSF funds numerous research projects to create green packaging, including:

- Using lignin – a primary waste product of the paper and biofuel industries – to create a biopolymer comparable to commercial plastics, but which will biodegrade in six months to two years. The biopolymer can be used for nursery containers for greenhouses, agricultural mulch and other applications.

- Developing biodegradable plastic cups by replacing petroleum-based polymers with reduced amounts of plant-based polymers that contain no harmful chemicals and generate much less CO2 emissions.

- Using waste methane gas (biogas) as a feedstock to produce a biodegradable polymer that can be converted into eco-friendly plastic products such as children's toys, electronics casings, water bottles and food packaging containers.

- Growing fully compostable, customizable protective foam packaging from mycelium, or the root structure of mushrooms.

"We're a big fan of supporting lots of different approaches to sustainability and hoping that at least one of those will win in the market,” said Schrag.