The power of portraits

Mona Lisa, Lady with an Ermine, Head of a Young Woman. Notice something? This list of iconic portraits features women. Unnamed women. And many of their stories remain untold.

It begs the question: What about the women who are left out of portraiture?

Portraits are powerful because they are historical records. They don't just show the talent of an artist or what a subject looks like — they capture the stories about change-makers and innovators. That's the mission of the Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, "to tell the story of America by portraying the people who shape the nation's history, development and culture."

Scientists and their discoveries are a major part of U.S. history and the American story. Their work in the past continues to influence U.S. science and technology leadership today. However, the exclusion of women, especially women of color, in scientific records is apparent.

Growing an art collection representative of the scientific community requires defining who was in the scientific community to begin with. For centuries, women and people of color in research were not seen or treated as equal contributors. These individuals were essential to the scientific process, often conducted extensive research, performed complex analyses, their important contributions were not even documented. Increasing representation through portraits is more than just finding works of art; it's about rewriting the historical narrative, and naming and crediting those who contributed to the most important discoveries of history.

Funding the Smithsonian

A large-scale project to address some of these inequities started from a unique letter of agreement between the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Smithsonian Institution in March 2020. The agreement allows NSF funds to support Smithsonian initiatives which would "enhance partnerships on STEM education, public outreach, research opportunities, and other mutually beneficial enterprises." The National Portrait Gallery received an award with a dedicated three-year detailee, science historian Lacey Baradel, to work at the gallery expanding the collection and educating the public.

Baradel has spent nearly the last two years at the gallery addressing inequality in the collection and increasing public knowledge on the gaps in representation. She first addressed one of the first and greatest challenges: incomplete historical records. She looked through the museum's current collection, then began the process of making a wish list of scientists to include. Once these gaps have been identified, her next challenge will be finding suitable portraits and deciding how to allocate limited resources.

Occasionally, the gallery commissions new artwork and collects recent creations, but the goal is to find portraits made during the subject's lifetime. Baradel searches high and low, emailing universities, estates and foundations — the places connected to the legacy, work and lives of the missing scientists.

Sharing with the public

As the first successful acquisitions are making their way to the gallery, Baradel explains the challenges with the public and has organized a panel to discuss the topic and solutions going forward.

"New Approaches to Representing Women in Science: In Conversation with Leila McNeill, Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, and Anna Reser," will be hosted by PORTAL, the National Portrait Gallery's Scholarly Center, on March 22, 2022.

The panelists will "explore the challenge of subverting established historical narratives and defining women's participation in the history of science." It will also touch on collaboration, technology and engaging the public. Registration is required, but the event is free. A recording will be available on YouTube after the event.

McNeill and Reser are science historians and co-founders of the independent magazine, "Lady Science," which was a unique magazine aimed at applying the rigor of academic platforms to public articles on an accessible platform. The success of "Lady Science" led McNeill and Reser to write “Forces of Nature: The Women Who Changed Science,” a book on the contributions of influential women in science throughout history told through portraits and stories across academic disciplines, continents and centuries.

The third member of the panel, Phingbodhipakkiya, is an artist with a background in neuroscience renowned for combining art and technology. In past exhibits, she used 3D printing to create busts of famous women in science. Her newest project is a series of public murals featuring women in science and uses a free app with an interactive augmented reality component.

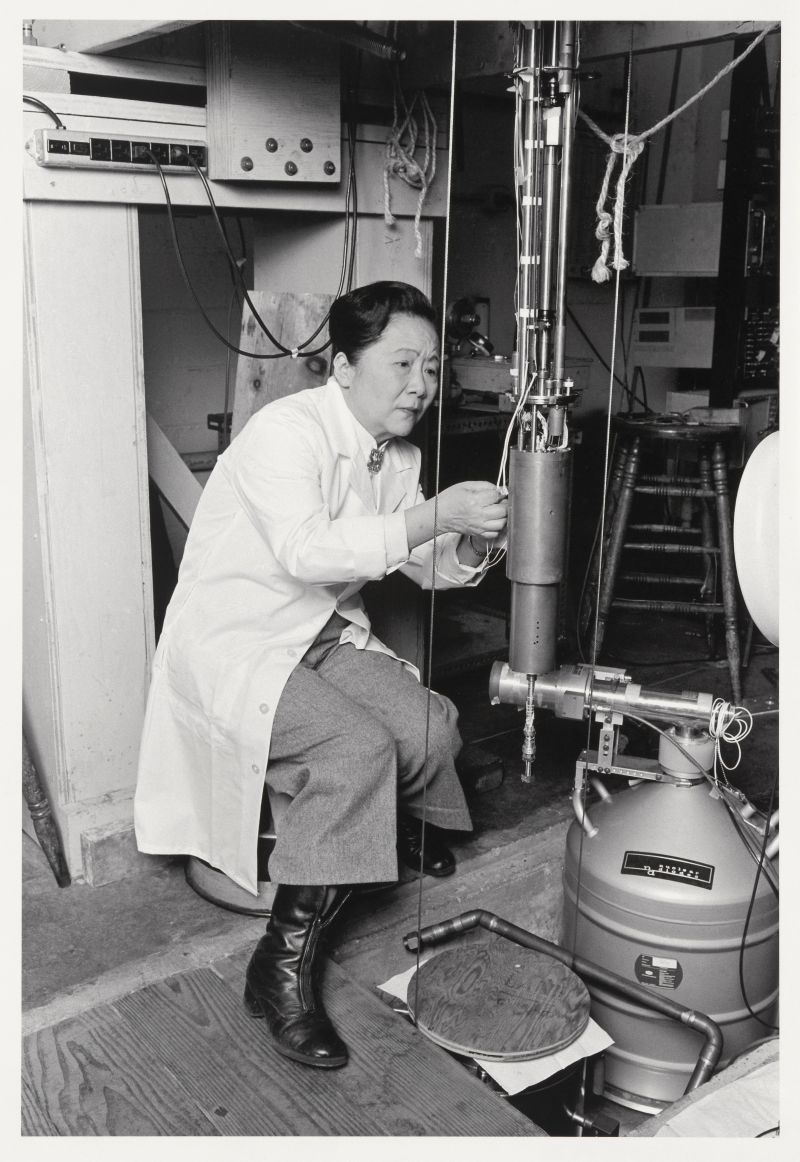

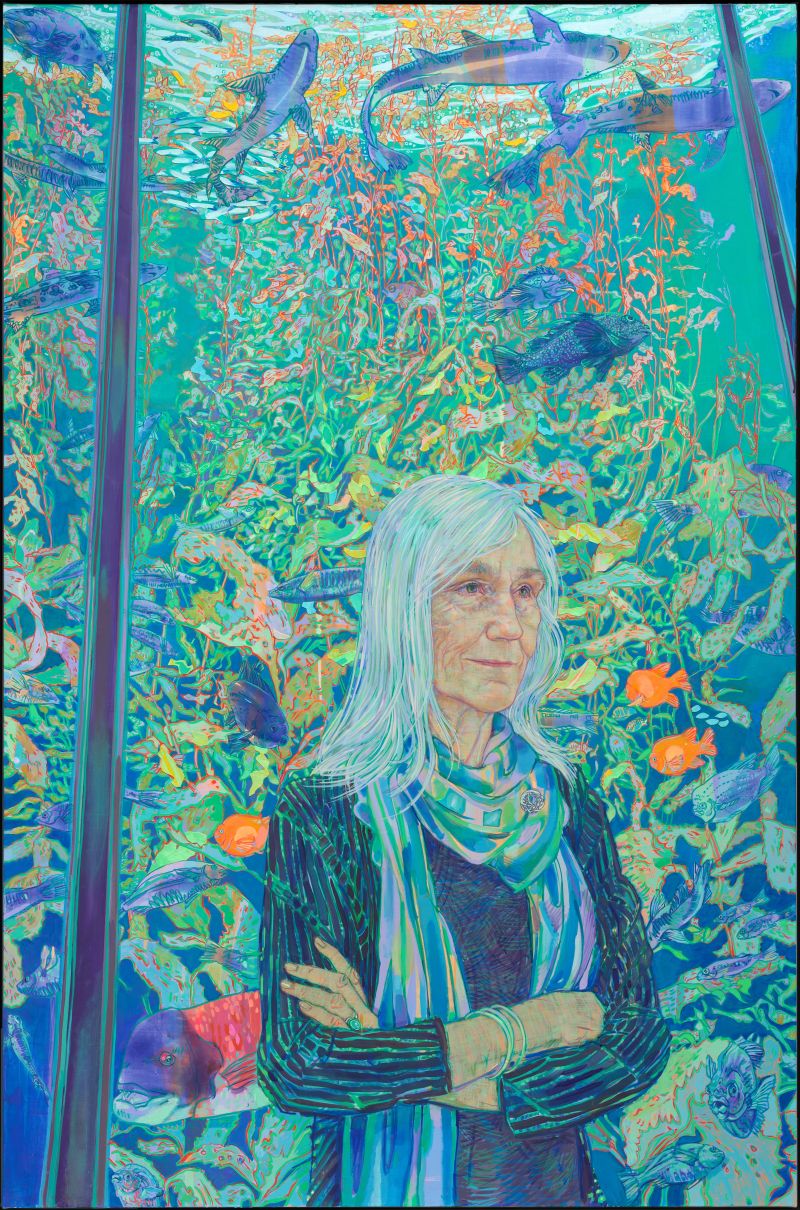

There will be more exhibitions featuring works Baradel is helping to bring to the gallery, however some portraits have already been added to the gallery's collection and are available to view virtually through the Google Arts and Culture project including Julie Packard, Maxine Singer, and Chien-Shiung Wu.

From university halls to family attics, the search continues to find, preserve, and celebrate the accomplishments of women in science who have been overlooked. Through greater inclusivity in portrait collections, future generations will know their faces, names and contributions.

If you know of an available work of art featuring a scientist who deserves more recognition, please contact Lacey Baradel at LBaradel@nsf.gov.