10 NSF-funded studies that show the challenges and complexities of climate change

In a complex dance, Earth’s climate affects, and is affected by, the sky, land, ice, sea -- and by life, including people. To understand climate change, which scientists believe may be one of the most important challenges humankind has ever faced, we need to comprehend Earth’s natural and human systems and how they interact. The answers may determine the future of life on our planet. For Earth Day, we look at 10 recent discoveries from U.S. National Science Foundation-funded climate change research and what they tell us about a warming planet.

1. Climate change forcing a rethinking of conservation biology planning

Creating and managing protected areas is key for biodiversity conservation. With changes in climate, species will need to migrate to maintain their habitat needs. Those that lived in protected areas 10 years ago may move outside those zones to find new areas that provide the climate and food they need to survive. Researchers looked at the amount of new protected areas in several regions, including areas where climate change is projected to be slower; areas where the terrain can shelter a high number of species; and areas that increase connectivity between protected zones, which allow species to move between them to escape adverse climate conditions. The study suggests that countries have not fully taken advantage of the potential of protected areas.

2. In a desert seared by climate change, burrowers fare better than birds

In the arid Mojave Desert, small burrowing mammals such as the cactus mouse, the kangaroo rat and the white-tailed antelope squirrel are weathering the hotter, drier conditions triggered by climate change better than their winged counterparts. Over the past century, climate change has pushed the Mojave's searing summer temperatures ever higher; the blazing heat has taken its toll on the desert's birds. However, the research team that documented the birds' decline also found that small mammal populations have remained relatively stable since the beginning of the 20th century. Using computer models to simulate response to heat, the researchers showed that small mammals' resilience is likely due to their ability to escape the sun in underground burrows and their tendency to be more active at night.

3. Scientists solve climate change mystery

Scientists have resolved a key climate change mystery, showing that the annual global temperature today is the warmest in the past 10,000 years. The findings challenge long-held views on the temperature history of the Holocene era, which began about 12,000 years ago and continues to the present. Using fossils of single-celled organisms from the ocean surface to reconstruct the temperature histories of the two most recent warm intervals on Earth, the researchers found that the first half of the Holocene was colder than in industrial times due to the cooling effects of remnant ice sheets from the previous glacial period. The warming was caused by an increase in greenhouse gases, as predicted by climate models.

4. Extreme melt on Antarctica's George VI Ice Shelf

Antarctica's George VI Ice Shelf experienced record melting during the summer season of 2019-2020 compared with 31 previous summers. The extreme melt coincided with record-setting stretches when local air temperatures were at or above the freezing point. The scientists studied the 2019-2020 melt season using satellite observations that can detect meltwater on top of the ice and in the near-surface snow. They observed the most widespread melt and greatest total number of melt days of any season for the northern George VI Ice Shelf. Understanding the impact of surface melt on ice shelf vulnerability can help researchers more accurately project the future influence of climate on sea level rise.

5. Tree rings and Iceland's Laki volcano eruption: A closer look at climate

By reading between the lines of tree rings, researchers reconstructed what happened in Alaska when the Laki Volcano erupted in 1783 -- half a world away in Iceland. Laki spewed more sulfur into the atmosphere than any other Northern Hemisphere eruption in the last 1,000 years. The Inuit in North America tell stories about the year summer never arrived. Benjamin Franklin, who was in France at the time, noted the "fog" that descended over much of Europe and reasoned that it led to an unusually cold winter on the continent. What happened to climate from the eruption reflects a combination of the volcano’s effects and natural variability. The research is helping fine-tune future climate predictions.

6. By the late 21st century, the number of people suffering extreme droughts will double

Scientists are undertaking a global effort to offer the first worldwide view of how climate change could affect water availability and drought severity in the decades to come. By the late 21st century, the global land area and population facing extreme droughts could more than double -- increasing from 3% during 1976-2005 to 7%-8%. More people will suffer from extreme droughts if a medium-to-high level of global warming continues and water management is maintained in its present state. Areas of the Southern Hemisphere, where water scarcity is already a problem, will be disproportionately affected. The researchers predict this increase in water scarcity will affect food security and escalate human migration and conflict.

7. Shark teeth offer clues to ancient climate change

A character in the movie "Jaws" said that all sharks do is "swim and eat and make little sharks." It turns out they do much more than that. Sharks have roamed Earth's oceans for more than 400 million years, quietly recording the planet's history. If a researcher like paleoecologist Sora Kim of the University of California, Merced, wants to "read" those records to learn about major global changes that took place 50 million years ago, she must decode the information stored in what remains of ancient sharks: their teeth. Teeth from the long-extinct sand tiger shark are providing new information about global climate change and the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates.

8. Scientists reconstruct 6.5 million years of sea level in the Western Mediterranean

The pressing concern posed by rising sea levels has created a need for scientists to predict how quickly the oceans will rise in coming centuries. To gain insight into future ice sheet stability and sea level rise, new findings draw on evidence from past periods when Earth's climate was warmer than today. To reconstruct past sea levels, researchers used deposits found in caves on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. The scientists determined that the extent of these unique deposits corresponds with the fluctuating water table, providing a way to precisely measure past sea levels.

9. Unsure how to help insect declines? Researchers suggest some ways

Florida Museum of Natural History entomologist Akito Kawahara's message is straightforward: We can't live without insects; they're in trouble; and there's something all of us can do to help. Kawahara's research has focused on answering questions about moth and butterfly evolution, but he's increasingly haunted by studies that sound the alarm about plummeting insect numbers and diversity. One of the culprits? Climate change. In response, Kawahara has turned his attention to boosting appreciation for some of the world's most misunderstood animals. Now, Kawahara and his colleagues outline easy ways to contribute to insect conservation, including mowing less, dimming the lights, using insect-friendly soaps and sealants, and becoming insect ambassadors.

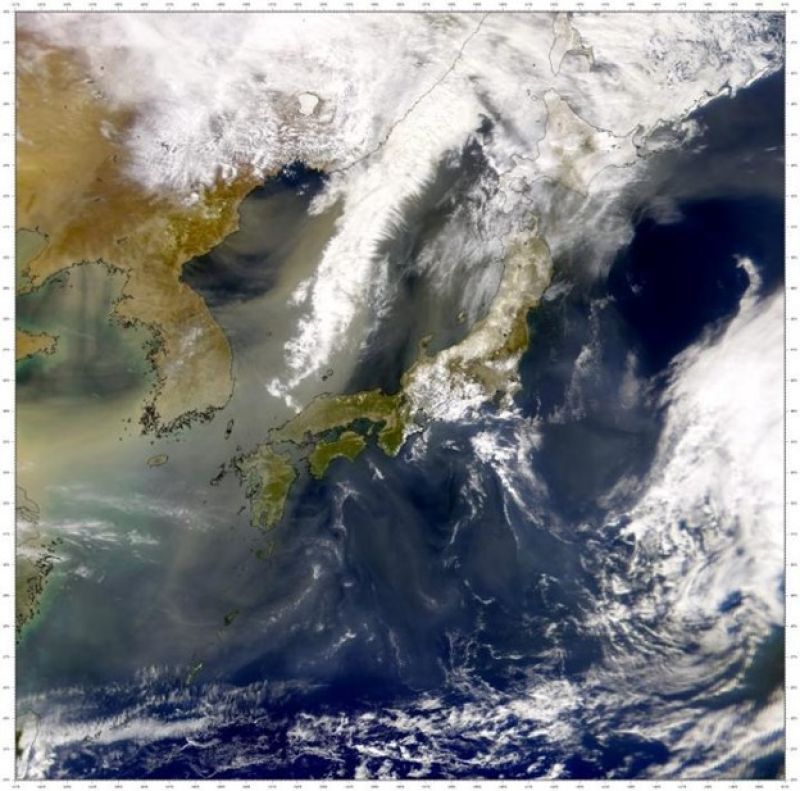

10. Will warming bring a change in the winds? Dust from the deep sea provides a clue

The westerlies -- or westerly winds -- play an important role in weather and climate locally and on a global scale by influencing precipitation patterns, affecting ocean circulation, and steering tropical cyclones. Assessing how they will change as climate warms is crucial. The westerlies usually blow from west to east across the planet's mid-latitudes, but scientists have noticed that over the last several decades, these winds are moving toward the poles. Research suggests this shift is due to climate change. Scientists developed a new way to apply paleoclimatology, the study of past climate, to the behavior of the westerly winds and found evidence that atmospheric circulation patterns will change with climate warming. This breakthrough in understanding how the winds changed in the past may show us how they will continue to in the future.