Genomic time machine in the sea

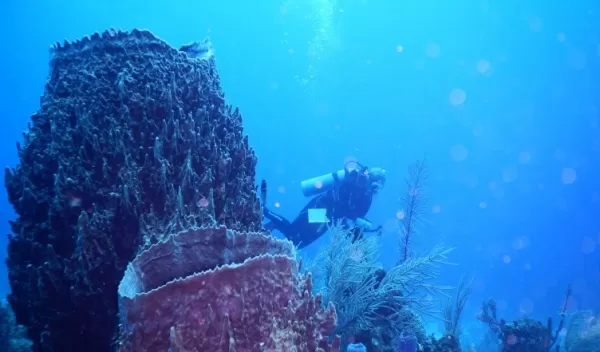

Sponges in coral reefs, less flashy than their coral neighbors but important to the overall health of reefs, are among the earliest animals on the planet.

New research by University of New Hampshire scientists and their colleagues peers into coral reef ecosystems with a novel approach to understanding the complex evolution of sponges and the microbes that live in symbiosis with them.

With this "genomic time machine," researchers can predict aspects of reef and ocean ecosystems over hundreds of millions of years of dramatic evolutionary change. The U.S. National Science Foundation-supported results are published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

"Coral reefs harbor a great diversity of sponges as well as corals," says Mike Sieracki, a program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences. "The sponges hold complex communities of microbes. This study shows that these communities offer clues to sponge evolution and function."

The significance of the work transcends sponges, scientists say, providing a new approach to understanding the past based on genomics.

"If we can reconstruct the evolutionary history of complex microbial communities, we can say a lot about Earth's past," says study co-author David Plachetzki of UNH. "This research could reveal aspects of the chemical composition of the Earth's oceans going back to before modern coral reefs existed, and it could provide insights on the tumult that marine ecosystems experienced in the aftermath of the greatest extinction in history, which took place about 252 million years ago."

The researchers characterized almost 100 sponge species from across the Caribbean using a machine-learning method to model the identity and abundance of every member of the sponges' unique microbiomes -- the community of microbes and bacteria that live in them.

The scientists found two distinct microbiome compositions related to different strategies sponges use for feeding and protecting themselves against predators — even among species that grow side by side on a reef.

The biologists found that one of the microbiomes extends back to when Earth's oceans underwent a significant change in biogeochemistry that coincided with the origins of modern coral reefs.

UNH co-authors include Sabrina Pankey, the paper's first author, and Michael Lesser and Keir Macartney. Other co-authors are at the University of Mississippi and the Universidad Nacional del Comahue in Argentina.