Co-occurring contaminants may increase North Carolina groundwater risks

Contaminants that occur together naturally in groundwater under certain geological conditions may heighten health risks for millions of North Carolinians whose drinking water comes from private wells, a new Duke University study finds. Current safety regulations don't address the problem, the scientists say.

"Guidelines for safe drinking water are normally based on one element or contaminant," said Avner Vengosh, a geochemist at Duke. "They tell us how much arsenic is okay to have in our water or the maximum amount of chromium that's safe. But what if arsenic and chromium occur together? That's something the guidelines aren't equipped to address, even though recent research suggests exposure to multiple contaminants may increase toxicity."

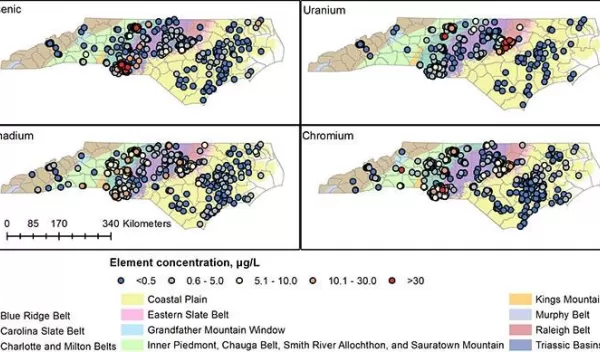

The National Science Foundation-funded study of four naturally occurring elements -- arsenic, chromium, vanadium and uranium -- in North Carolina groundwater wells highlights this disconnect.

"Around 84% of the wells sampled in the Kings Mountain Belt and the Charlotte and Milton Belts of the Piedmont region contained concentrations of vanadium and hexavalent chromium, in its more toxic form, that exceeded health recommendations by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services," said Rachel Coyte, a researcher at Duke who led the study.

Of the four elements studied, vanadium and chromium were found to co-occur most frequently.

The Kings Mountain Belt and the adjacent Charlotte and Milton Belts are geological formations underlying the western Piedmont. They cover a combined area that extends northward from Charlotte and its suburbs to the Virginia border.

The fact that 84% of the nearly 1,500 wells sampled in this area contained levels of both vanadium and hexavalent chromium in excess of state health recommendations is reason for concern, Vengosh said, especially since these recommendations are based on epidemiological studies of risk factors.

Coyte and Vengosh published their paper in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

"Research on these chemical elements in regional groundwater benefits North Carolina, other eastern states, and those who study similar chemistry in other regions," says Enriqueta Barrera, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "Groundwater is a valuable resource. Understanding its geochemistry will greatly contribute to long-term public health planning."